Cry Of The Wounded

Text and photographs © Asher Imtiaz

Poetry © Mari Reitsma Chevako

Published in The Living Church in July 2020 issue.

Minneapolis, May 27, 2020

One of my heroes, the photographer Sebastião Salgado, has said that when producing a body of work, a photographer must consider that “Photography is not objective, It is deeply subjective.” He went on to say that his own photography “is consistent ideologically and ethically with the person I am.” In other words, when you are out to photograph, you also bring with you the themes you carry inside yourself. I have always reflected on that idea, and I ask myself, “What themes do I carry inside myself?”

From the early days of my photography, I decided to focus my camera towards religious and cultural minorities because I belonged to one, living as a Christian in a 95% Muslim country. I have also wanted to counter some of the narrative western photographers have appropriated in my part of the world. Being a photographer of minorities and documenting people living under pressure in my home country helped define the themes I have carried inside myself. After moving to the United States, I continued exploring those themes as I started documenting the lives of immigrants in the US, mainly refugees and asylum seekers.

A few friends have looked at my photographs in recent years and suggested that I should document stories in some black neighborhoods. After all, I live in Milwaukee, which is considered the most segregated city in the United States, and it is ranked the worst city in the US for racial equality. My response has been that I am not the right person to tell their stories. A black photographer who understands their own people should do that. I reasoned that as someone on the path to immigration, I should just focus on immigrant stories.

I was challenged again to capture the stories of African Americans on Memorial Day this year. I was visiting my friend in Minneapolis, and I was planning to walk in the 80 degree weather, to go to a park and relax in a hammock, to read poetry and to enjoy a barbeque . At least that was the plan. Then, on May 26th my friend told me that a video came out of a black man who was killed by a police officer. I saw the video briefly, which I found deeply disturbing, and then the protests began. All this was unfolding quickly a block away from where I was staying.

Earlier this year, during lent, I wrote a devotional for my church publication in which I was reflecting on the idea that “we all play some role in the suffering of people. Because of our actions and inaction, real lives are affected.” The devotional kept coming back in my mind, and as I found myself among suffering people, among ashes and dirt, I knew I had to respond.

Those following the news know what happened the rest of that week. It was my first time in such protests, and I realized I was not ready at all. The very first night I experienced tear gas, and the second day I was hit on my face with a rubber bullet, an inch under my left eye. I thank God it missed my eye. After 10 days, the bruise left by the rubber bullet disappeared from my face. But what remains is the thought, “What should I do with what I see with these eyes, and how can it help? What is the right thing to do?”

As I stood among the protestors, I heard the cries of wounded people and witnessed their pain. They were angry and grieving, and not just because of the death of one man, but because of many deaths over the generations caused by racist systems.

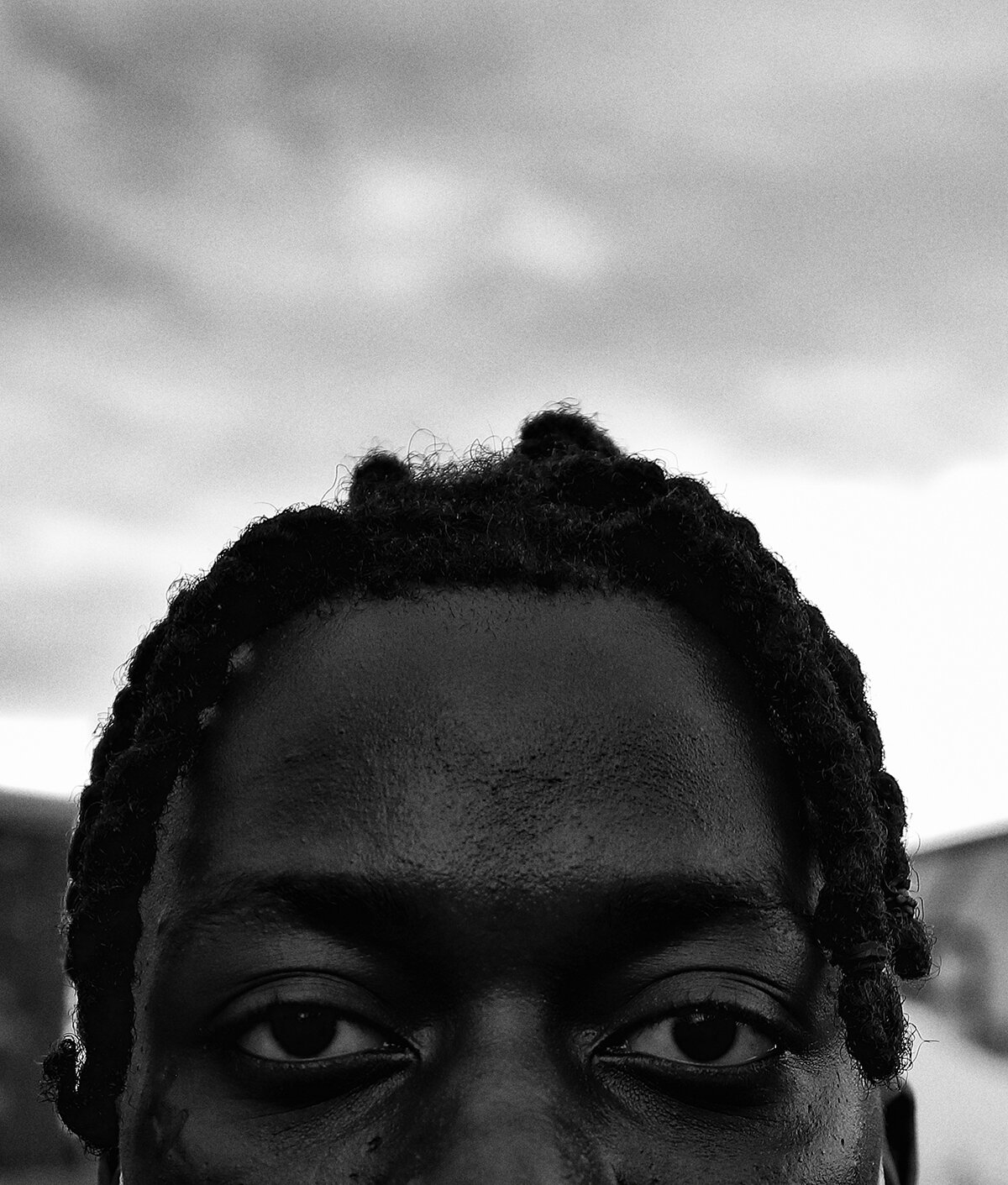

“If you had looked into his eyes, you would have known.”

In his book The Wounded Healer, Henri Nouwen narrates a story from which I’ve taken a thought I carry with me: “If you had looked into his eyes, you would have known.” The assumption here is that we recognize our own brokenness and woundedness. Only then can we become a bridge that allows us to know the pain and woundedness of another. We step into other people’s wounds out of our own woundedness.

When I look someone in their eyes, they look back. When they see through the camera, they realize that fraction of a gaze is for me, but that questioning gaze is also for everyone who will witness the photograph. In that moment, they are asking me to honor them and who they are and what they represent. I think honoring a person standing in front of you is always right.

God is at eye level.

Minneapolis, June 02, 2020

Minneapolis, June 02, 2020

Minneapolis, May 29, 2020

Minneapolis, May 29, 2020

Minneapolis, June 02, 2020

The Earth Beneath Your Feet

© Mari Reitsma Chevako

Milwaukee, May 29, 2020.

(“In this time of human quiescence, the creaking of some potentially dangerous faults may be detected better than ever,” NY Times, 4/8/20)

Gone the hum of your human endeavor.

Your great cities lay quiet,

your machines no longer whir,

your games and music have ceased.

Listen: the earth beneath your feet

is heaving and groaning.

Can you hear the migratory birds

trilling each to each? Indeed.

But what does it matter

if you still won’t believe

a black man can thrill

to the sound of a yellow warbler?

Leash your damn barking dogs.

Call off the police.

You have a moment here,

your volume reduced,

your cacophony hushed,

to hear the fault lines creaking,

uphold justice, defend the oppressed.

But mostly you mark

the sound of your own heart, the swish of air

in and out of your lungs.

You check your pulse,

you measure your breaths.

But what of the breaths

of the men on the pavement

knees on their necks?

You boast that you stand

on the right side of the divide,

the right side of the country,

the right side of the street.

You take up your guns

your superior red blood surging,

pledging an oath to your country, yourself,

as if when the moment comes

the earth won’t swallow you up.

Who asked this of you,

this trampling, this restless to and fro,

demanding rights in my name?

Untie the blindfold from your eyes

and wind it around your lips.

You are not immune.

Away from me, away.

I don’t dread what you dread,

nor fear what you fear.

I make the earth tremble in place

and shake the heavens on high.

And you, white Christian,

festooned with your star-spangled shirt—

I never meant your skin to carry

the privilege you claim. Even you

are made from ashes and dirt.